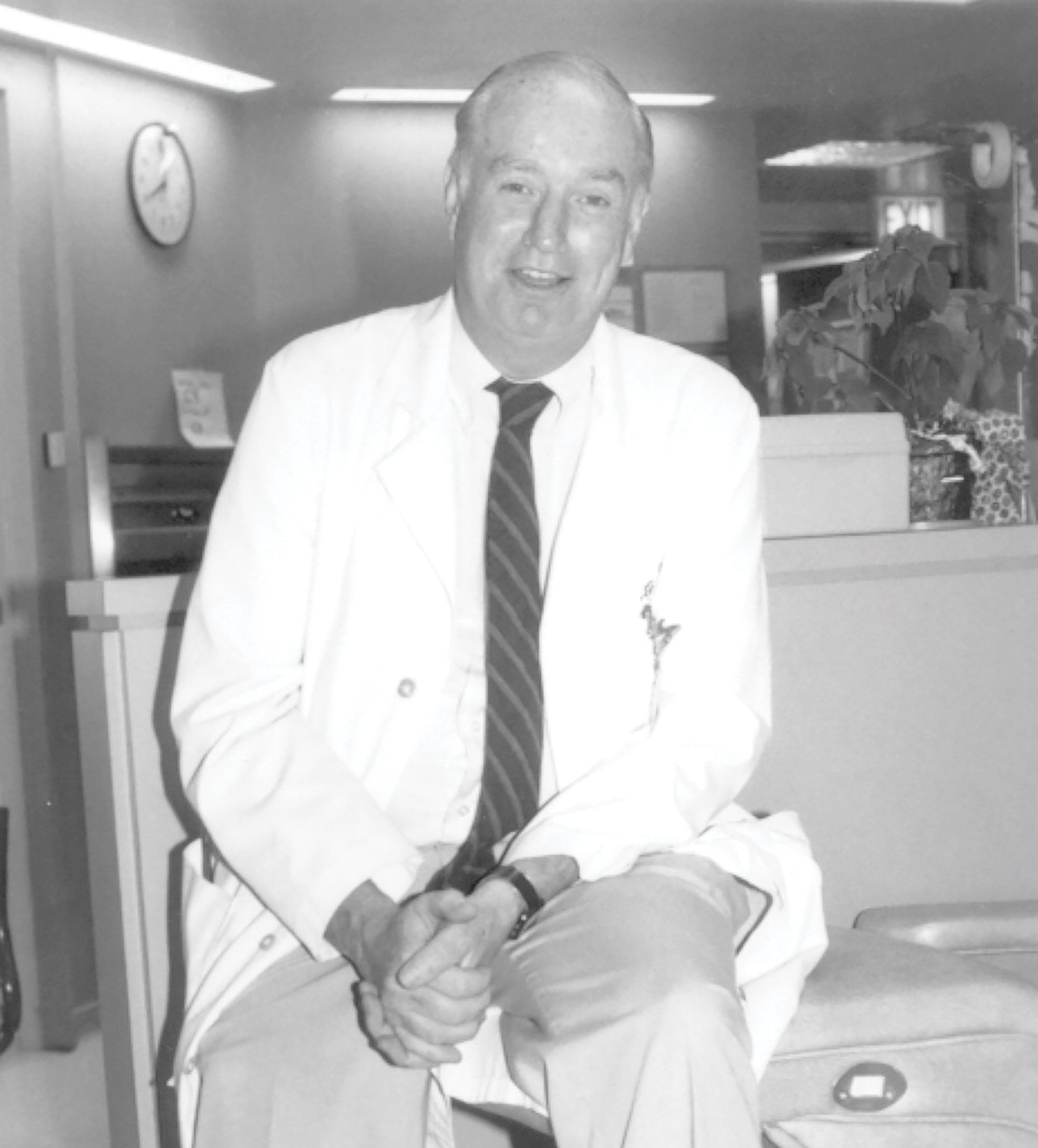

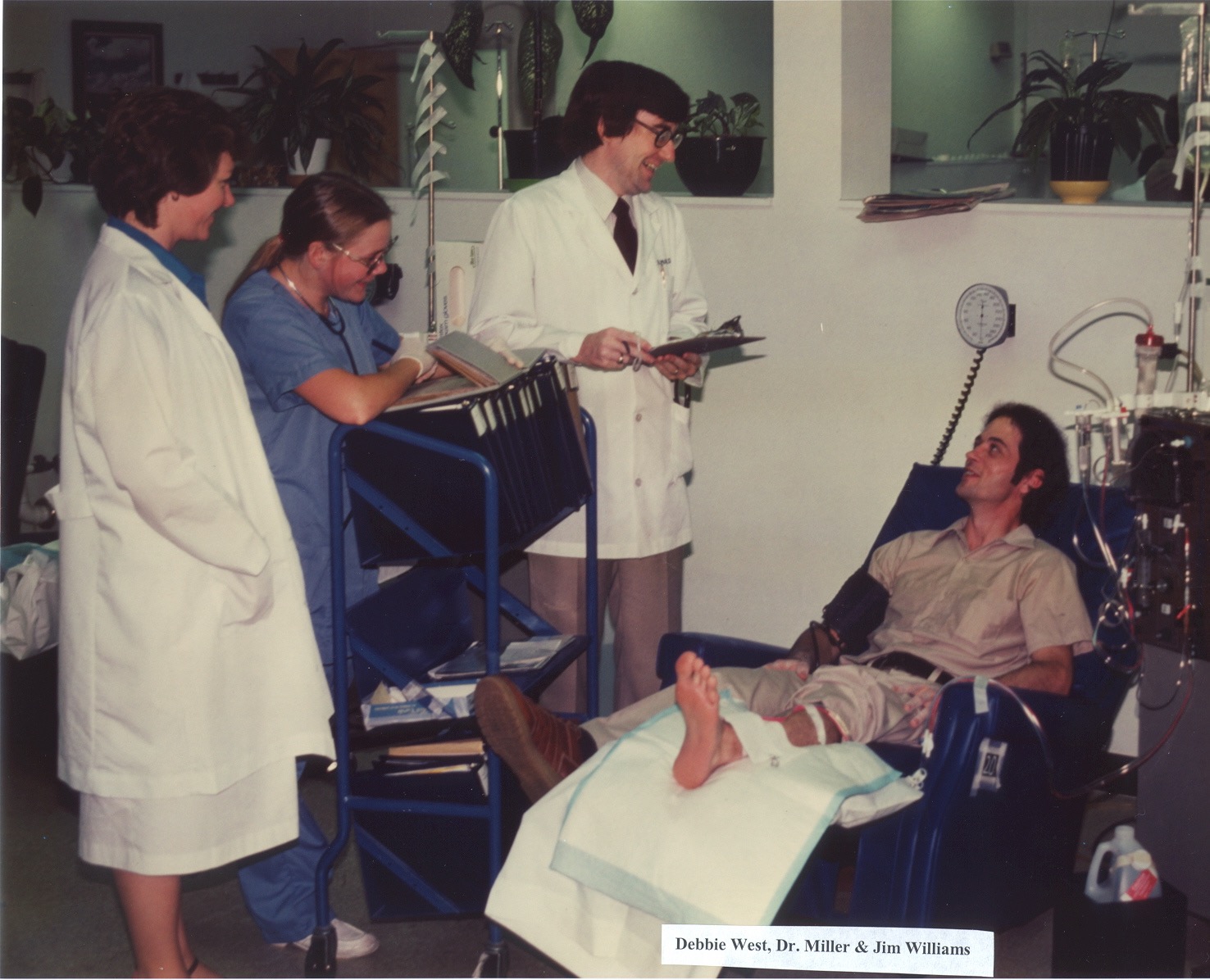

DCI was founded in 1971 in Nashville, Tenn., as a not-for-profit dialysis provider by nephrologist Dr. H. Keith Johnson. At that time, there was no Medicare funding for dialysis, and most patients did not have insurance coverage for dialysis. This meant that many patients couldn’t afford treatment and would face the difficult choice of mortgaging their homes, selling their farms, spending their children’s college funds, or worse yet, returning home without treatment.

Our Story

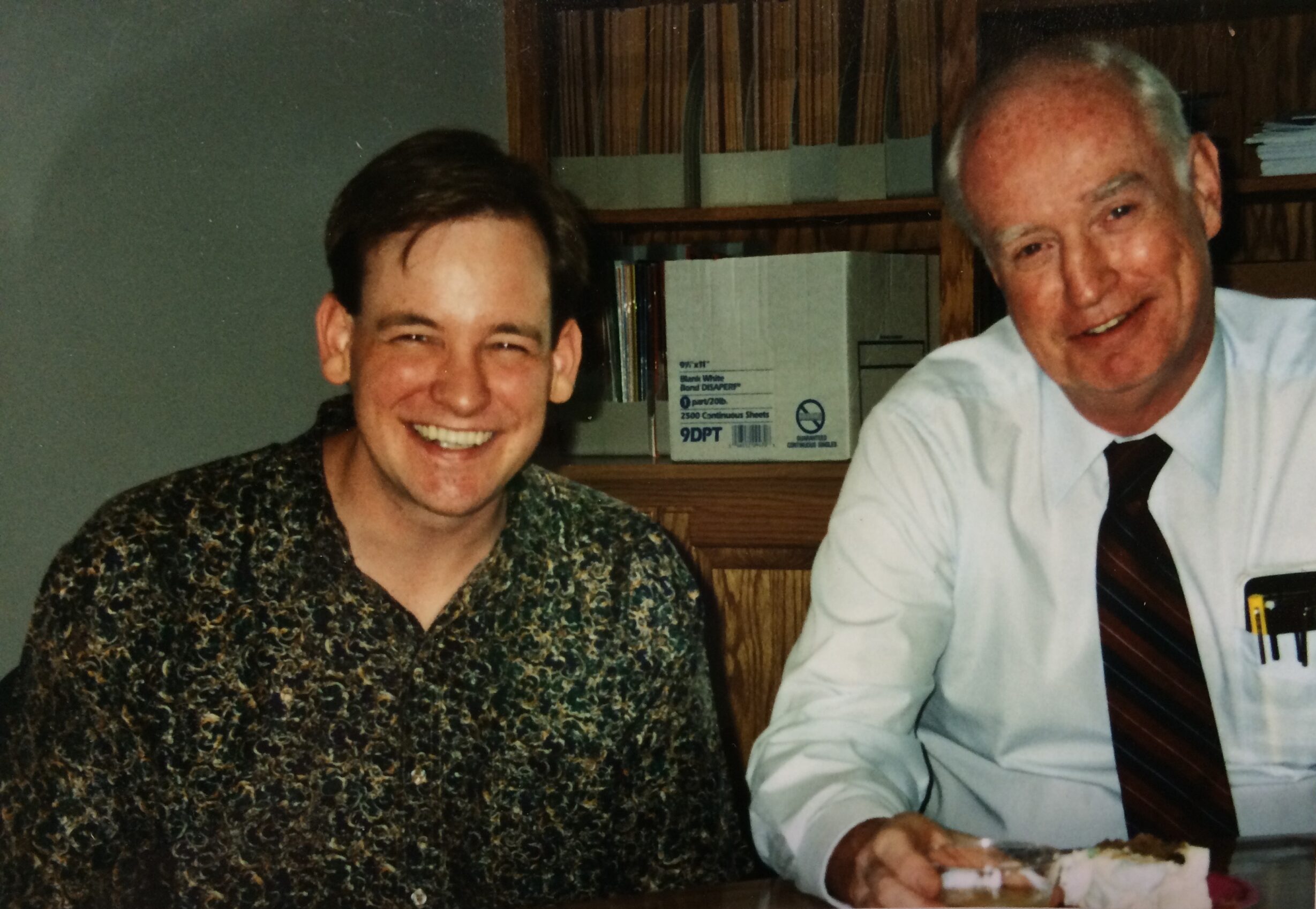

Dr. Doug Johnson and Dr. H. Keith Johnson